Farming & Nature Conservation (FNC) was the last project to be confirmed for Tranche 1, eventually running from 2017 – 2020. The team aimed to find ways to improve native biodiversity on sheep and beef farms, while improving the functioning of the farm as a business.

Former FNC co-lead David Norton (University of Canterbury) says an awful lot came out of the programme besides scientific outputs.

“The desire to work with farmers one-on-one [to improve biodiversity on their farm], do research to underpin ecological restoration, and to understand landscape processes on private land,” he says.

The FNC project also identified key gaps in the field of agroecology, which led to the establishment of two new projects looking at different aspects of native biodiversity on farms.

Leaving a legacy

In 2019, Auckland University of Technology (AUT) and Te Uru Rākau teamed up to co-fund the AUT Living Laboratories Programme – an investment that would go on to win the 2021 AUT Vice Chancellor’s Research Team Excellence award. Former FNC co-lead Hannah Buckley designed the long-term ecological experiment with fellow AUT staff Bradley Case and David Hall.

She says “We wanted to test some of the ideas that emerged from the FNC project.

“There are so many questions around the performance of native woody species in agricultural landscapes. We make these sweeping statements about the performance of native species, but no one has really done comprehensive, comparative studies on growth rates in different environmental conditions.”

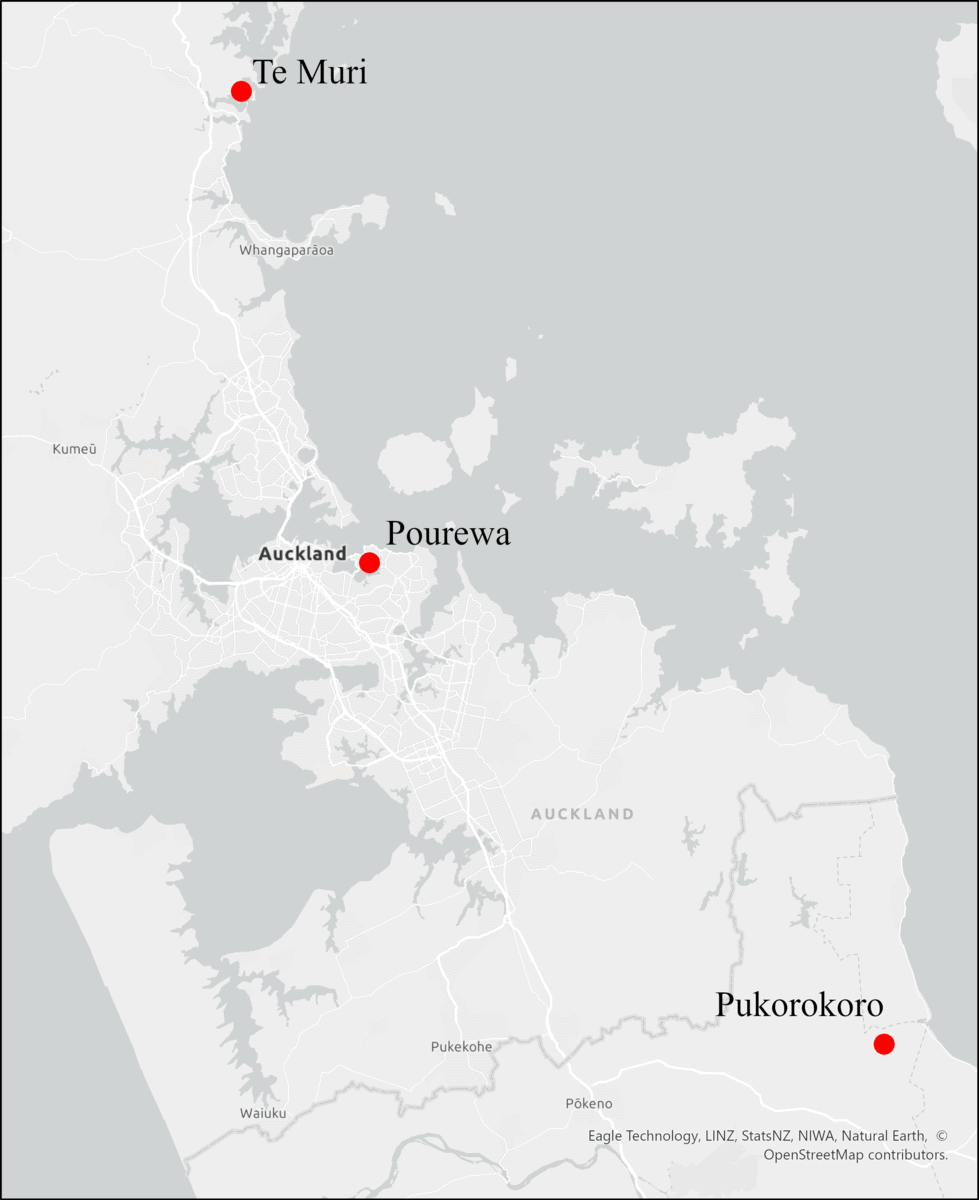

The complex setup of the Living Labs programme has involved tens of thousands of plants being established at two locations in Auckland and another in northern Waikato. Each site is home to ‘nurse’ plants (the native species usually seen when a paddock starts reverting to native bush), combined with later successional species (usually only present in mature forest).

Across the three sites, the research team are experimenting with different restoration design factors that could affect the growth of the trees. Planting density, irrigation and the stature of the nurse plants could all influence the success of a restoration project.

But it’s not just about the plants – Hannah says they’re also looking at ecosystem function.

“We want to measure how ecosystem functions associated with restored biodiversity change over time, so we’re monitoring soil biota, soil processes, water quality, birds, and invertebrates, in addition to monitoring the success of over 30,000 planted trees.”

With the project covering more than nine hectares, the team will be able to monitor the effect of environmental factors, such as the slope of the land and distance from the nearest native bush patch.

“At one of the sites, Te Muri, we’ve specifically looked at the cost of the restoration setup,” Hannah says.

“We varied the density of the plantings. So, the upfront cost of low-density plantings is much lower, but how does this change the biological outcomes? Obviously it’s going to take longer to get a closed canopy, so how much does that cost you in weed management and other treatments?”

This information could save land managers huge amounts of money in the future.

Ecological monitoring is normally done at the ‘plot’ level – calculating things like biomass per hectare. But the Living Labs team wanted finer-scale data to improve understanding of biomass accumulation on individual trees.

Hannah says “We know that individual tree growth depends on competition with other plants, in addition to microhabitat effects.

“So this finer-scale monitoring is going to allow us to tease out those different, small-scale effects compared to the much larger-scale effects, such as droughts or soil type, which may vary among landscapes. This will be useful data, but it’s a lot of work; that’s why it’s a long-term study!”

It takes a village

A brainchild as large as this could never exist under just one research team. The staff and students at AUT have been partnering and collaborating extensively with other universities and the communities around them.

The first site, Pourewa, was set up in partnership with Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei. After about 30 years hosting a pony club, the 2.1ha in central Tāmaki Makaurau was returned to mana whenua, who set about restoring the ngahere – recloaking the whenua.

At the conception of the project, both parties ensured their visions and aspirations were well-aligned, so they could mutually enable each other to reach their goals. Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei mātauranga-a-iwi (region-specific traditional knowledge) has been invaluable for this site of the Living Labs project.

The second site, Te Muri, is a retired farm owned by Auckland Council. The Council and Ngāti Manuhiri have a co-governance plan for the area, and their joint goals matched well with the aim of Living Labs.

The last site, Pūkorokoro, was established in September 2022 and is owned by Te Whangai Trust. This is a social and environmental enterprise that assists the long-term unemployed, youth and people at risk.

Hannah says “They have a nursery and provide work and opportunities for young people . . . this has a great social element to it.

“So the AUT Living Laboratories Programme is not just a long-term research study. It’s also a long-term education and community resource. It’s a legacy resource for the landowners and New Zealand as a whole.”

The entire Living Labs project has been set up to be open access.

“Part of our arrangement with the landowners is that all of the data will be open access,” Hannah says. “It’s all set up in a way that if others want to come and use the sites for their own research, adding experimental treatments, adding different kinds of monitoring . . . we’re very open and supportive of that.”

International connections

Rooted firmly in their local communities, the Living Labs team have also become a key component of an international study.

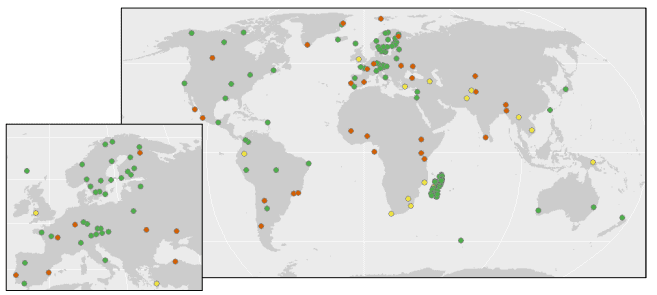

LIFEPLAN is run out of the University of Helsinki in Finland and aims to establish a reliable state of biodiversity around the globe. It was launched in 2020 and will run for six years.

“They have 100 sites around the world and we are the only New Zealand site,” says Hannah.

“They’ve sent us biodiversity monitoring equipment and protocols that are being used globally in a consistent way.

“We’re using state-of-the-art, high-tech monitoring methods, including wildlife cameras and acoustic recorders. There’s even an air sampler to measure bioaerosols such as microbes and pollen. Sampling is done every week for the whole year.”

Each research team has been instructed to take measurements for one year at an urban bush site, and then take them for one year at a ‘natural’, or rural, site. This is repeated three times at each site and all the data is sent to the lead research team in Finland.

Hannah says “This year, we have partnered with Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei and Auckland Council to sample within Kepa Bush (next to Pourewa) and next year we will switch to the natural bush patch at Pūkorokoro, then back again. It’s pretty intensive but it’s vital to add data from New Zealand into this global context.”

The information from the LIFEPLAN study will complement that of Living Labs, giving the team baseline data from the adjacent bush patches, which they can compare to their restoration sites.

You can watch a webinar on interim results from the LIFEPLAN programme by clicking here.

Listen to the Living Labs team on Our Changing World (RNZ) by clicking here.

Getting help on the ground

Throughout the duration of FNC, team members heard a common theme of questions from many farmers, farm consultants and regional council staff: where could they find reliable information about on-farm biodiversity?

Sometimes this could be found on a specific website or in an old booklet. Sometimes it was hidden in a scientific journal – locked behind a paywall. And far too often the information simply didn’t exist – no one had been able to garner funding for the most basic of questions about native biodiversity on farms in Aotearoa.

Images by Stacey Bryan (left and right) and David Norton (centre).

So, as the FNC programme was nearing an end, co-leads David and Hannah gathered colleagues from across the pastoral farming sector to ask one more question: how do we get farmers the information they need to make the best choices for their farm and the biodiversity on it?

Thanks to bridging funding from Pathways to Ecosystem Regeneration, the small group of determined industry experts secured support from MPI for a pilot project called Farming with Native Biodiversity.

David says the project has four main pillars:

- Return the pride to farming

- Find practical solutions that will lead to tangible outcomes

- Create win-win outcomes for biodiversity and farms

- Sustainable farming becomes the norm

“That’s a massive swathe of things,” he says, “but I think what we’re trying to do is really just start a process to develop some of the support for farmers that is needed in the biodiversity space.

“It’s a short project – it only runs for 20 months, so it finishes mid-2023.”

The project is hosted by NZ Landcare Trust – a well-known organisation working nationally with rural communities.

It is funded through the MPI Sustainable Food and Fibre Futures Fund, which requires researchers to team up with commercial partners. In this case, Silver Fern Farms and Living Water (DOC and Fonterra) were happy to come on board and provide the co-funding.

David says the original FNC project laid the foundation for this to happen.

“Both of those relationships came out of the earlier BioHeritage Challenge project. We worked with Matt Harcombe (now at Silver Fern Farms) when he was at Beef + Lamb NZ. Some of those early [FNC] connections we made were really important here.”

Silver Fern Farms has provided an introduction to 40 exemplar farms from across Aotearoa, which are being visited by the team’s three early-career ecologists. This will ensure the pilot project resources are well-grounded in real farm life.

The project ecologists are working directly with farmers to help develop farm biodiversity plans, find out what biodiversity information the farmers need, and the best ways of getting it to them. A mātauranga Māori advisor also guides the work to ensure the resources and tools developed include Te Ao Māori perspective.

“A massive outcome from this project is that, by the end, there will be three ecologists who have experience, credibility, and an ability to do this work with farmers in the future,” David says.

“Who knows who they’ll work for, whether they’ll work for themselves, MPI or consultancies, but we’re going to have some ecologists who will have the ability to listen to farmers, talk to farmers. It’s a massive gap at the moment – we just don’t have those ecologists out there.”

The team are also working with Fonterra’s sustainable dairy advisors, who are traditionally trained in environmental management.

David says some farm consultants are struggling to help their clients with the biodiversity legislation that’s coming their way. If this new team can help to upskill consultants in this space, that’s a win for everyone.

The third branch of the pilot project comprises resources that can go beyond the initial 40 farms.

Using the feedback from people on the ground, the team will develop a set of resources that give farmers reliable, realistic information and advice about how to care for the native species on their land. These will likely be a mix of digital and physical documents, videos and podcasts.

The future of biodiversity research on farms

The link between both spin-off projects is that they’re trying to find solutions for a real, on-the-ground situation.

David says “We’ve got something like 20,000 pastoral farmers in New Zealand, most of whom have biodiversity on their farms. They need support to manage it, and we need to understand the ecology that underpins that support.”

At this point, what’s missing is the landscape-scale work.

“From a science point of view, that’s probably the thing we know least about. When we do one thing in the landscape, how does it affect the functions of biodiversity at a landscape scale?”

Hannah says we don’t have a lot of this information, particularly for native species.

“We’ve done a literature review that’s still in the works,” she says, “it’s looking at what we know about native and exotic animal species in New Zealand’s agricultural landscapes. How they move around within the landscape and their home ranges.

“We discovered that we know surprisingly little. And we know much less about our native species than we do about introduced species! That’s a disappointing lack of basic natural history and ecology knowledge, considering pastoral landscapes make up half of New Zealand’s land area.”

With a huge makeover to the science system currently underway, this is the sort of research Hannah would like to see addressed.

As the Head of the AUT School of Science, she thinks we need to address key gaps in our “nuts and bolts” scientific research, in addition to pushing high-impact publications.

“Research on the restoration of native forest within New Zealand agroecosystems also needs to be done in the context of Predator Free 2050. We need to understand how both native and introduced animals will respond to changes in landscape vegetation, with and without changes to pest animal food webs.”

David says to make the best choices for the country, we need to consider land use configuration within the wider landscape. Only then will we be able to have viable populations of the species, like kārearea, kiwi and kererū, that people care about and want to see across rural Aotearoa.

BioHeritage is proud to be funding a Postdoctoral Fellowship within the AUT Living Laboratories programme, to help continue their investigations into ngahere restoration. Applications for this position close 15 November, to find out more and apply click here.

– Stacey Bryan