Toitū te Ngahere “bounced out” of Toi Taiao Whakatairanga, a research project commissioning artists to connect with the topic of ngahere ora, says Ariane Craig-Smith, project co-ordinator. “Toitū te Ngahere brings together science, mātauranga Māori and arts to see how these different ways of knowing support each other to help us learn about our forest ecologies. We want the kids we’re working with to look at that big picture of forest health and the role that they can play, and to share the learning they’re doing with the wider community. And we want art to be a big part of that,” Ariane says.

Collaborating with Toitū te Ngahere, Konini Primary (a mid-decile school in west Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland) were invited to make art works as part of their journey, and to explore what environmental kaitiakitanga (guardianship) looks like for them and their community. This year, the students wanted to create artworks to share for Matariki.

Both Matariki and kaitiakitanga were already established parts of the school’s culture. Ariane says Konini Primary’s sense of pride and care for their ngahere was already “just incredible”.

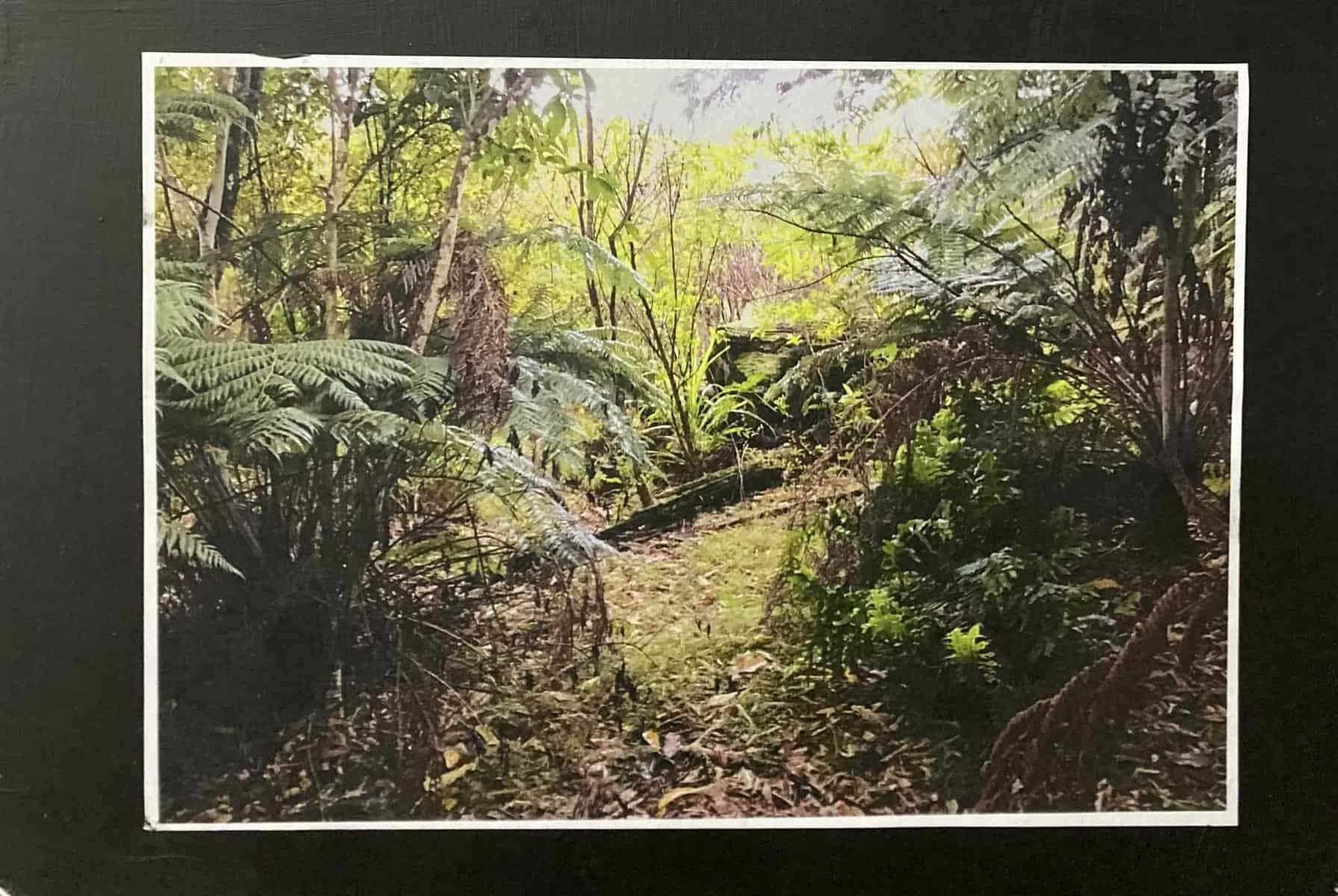

“We’re really lucky to have half our grounds in native bush,” says Konini principal, Andrew Ducat. The schools custodianship of this block of forest means they are able to “embed their learning in an authentic way,” says Andrew. “What we’re seeing in the children is that an emotional connection to the learning task gives far more rich and lasting learning opportunities.”

School events are popular at Konini Primary – parents “turn out in droves”.

“[The students] had this real clear vision that they wanted to share the art that they were making at their Matariki event,” says Ariane. As a practised arts curator, Ariane was a fitting mentor to support them achieving their vision.

Right: ‘Jungley Green’, photograph taken in the Konini ngahere by student Lucas. “This photo captures the healthy and thriving relationship between the trees and their canopy. It is important to allow the forest to be healthy.”

Images thanks to Ariane Craig-Smith.

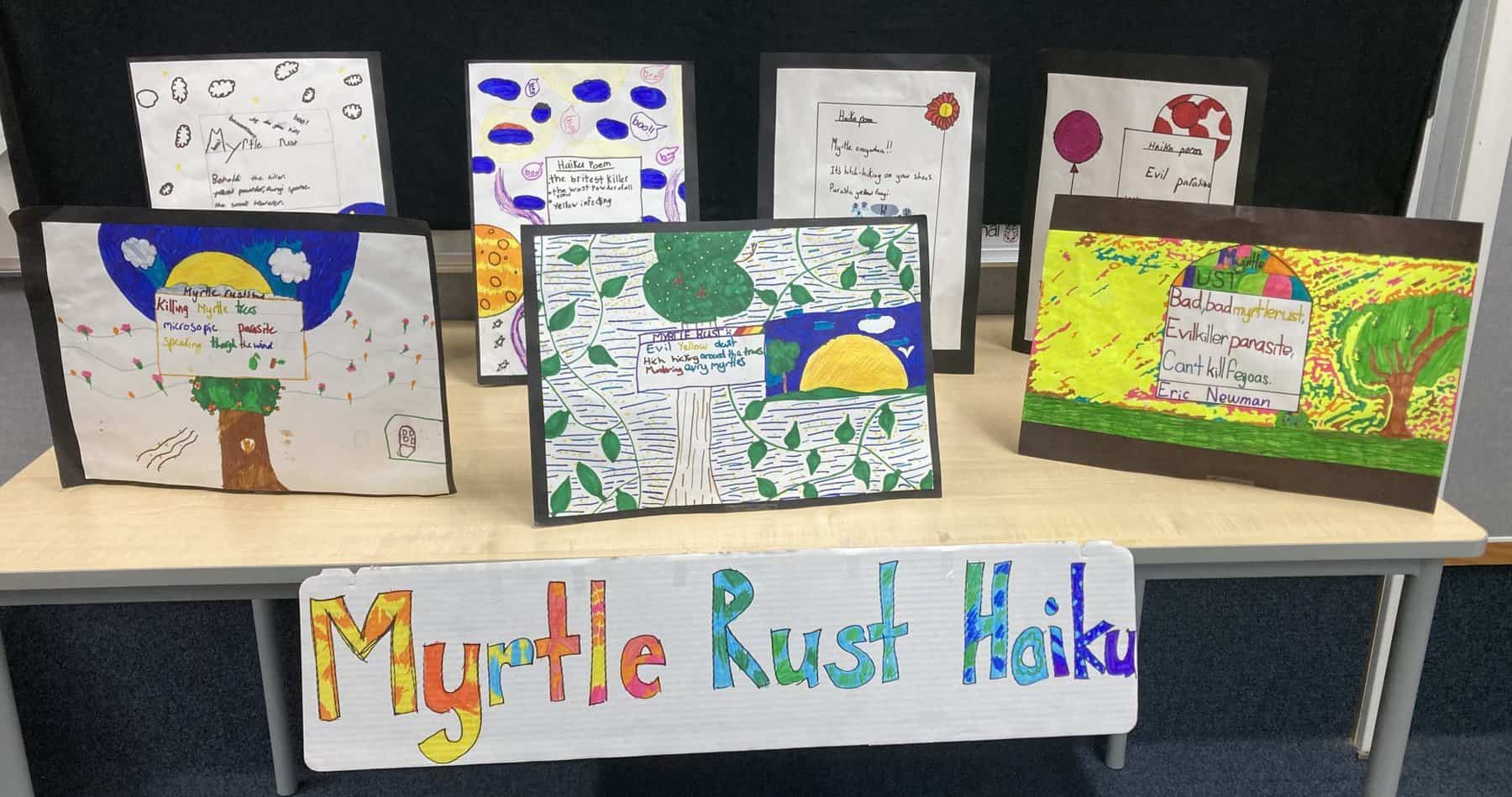

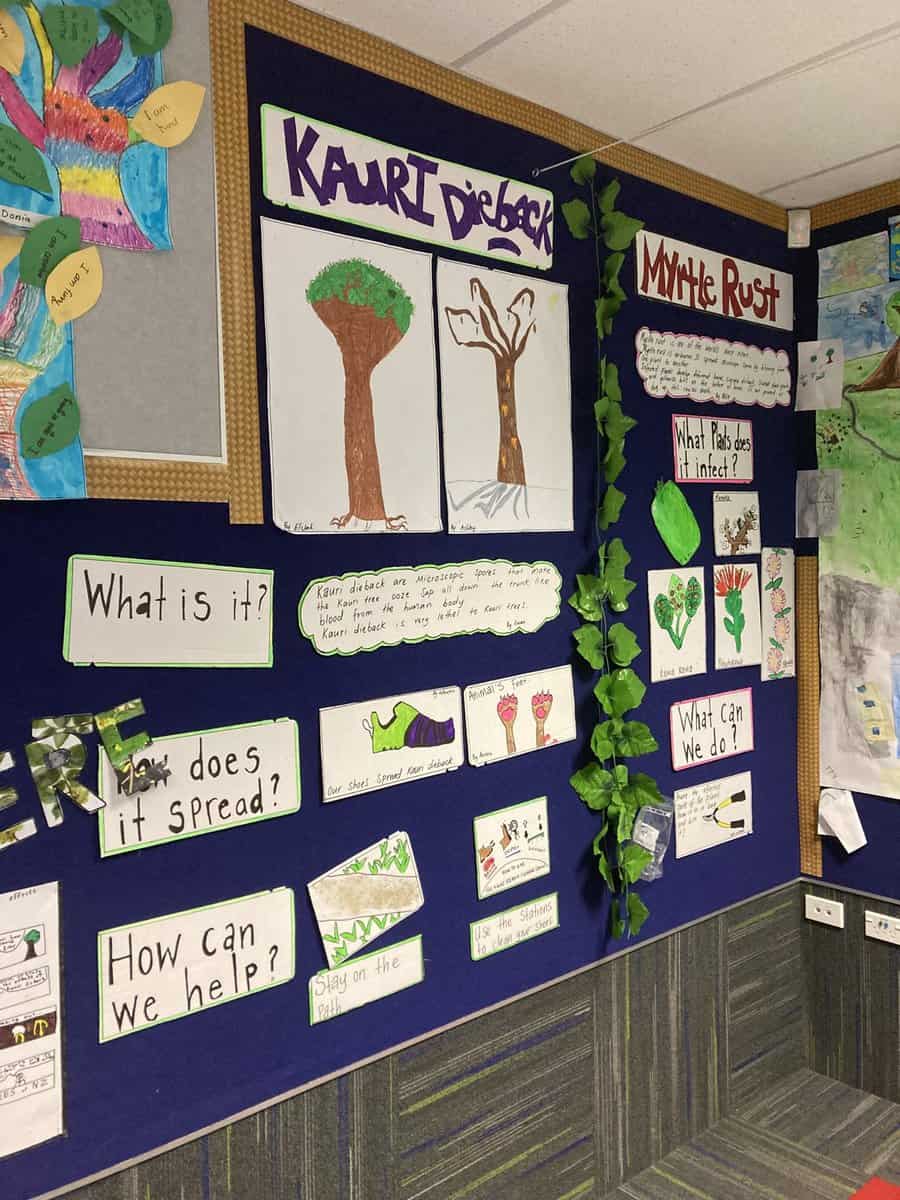

When it came to creating the art works, sessions ran fortnightly. Adults offered solidarity and soft support for student-led investigations. Team members guided students in photography and composing haiku. Other works were informed by a local tohunga with expertise in the tradition of Māori storytelling, and via Zoom interviews with scientists.

An audio artist issued a brief to students asking them to use recorders to capture sounds that identified their bush (like water droplets from their waterfall) to allow them to create virtual walk-throughs of their ngahere. The students were particularly excited by the introduction of this new creative tool.

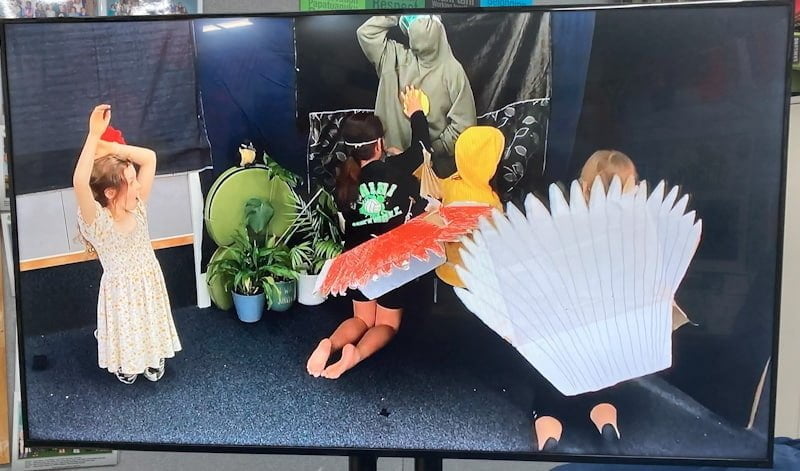

Another class was more interested in creating dramatic scenes describing the life cycle and spread of myrtle rust. These four scenes were filmed with custom-created props and were presented on the night of the event. “[The videoed scenarios] are funny, improvisational, just delightful and brilliantly communicated,’ says Ariane. “There’s a little scenario of birds landing and pollen spores getting stuck. There’s a scenario of myrtle rust spread originating from a garden centre. They really understood those messages and they turned them into something really inventive.”

Photography students edited and wrote about their work, “beautifully expressing their feelings about caring for the forest,” says Ariane.

Each class wove their Toitū te Ngahere research into the greater schools research around Matariki. On the evening of the celebration their classrooms becoming galleries, with the artworks displayed throughout, alongside kapa haka and dance.

Image thanks to Ariane Craig-Smith.

With the work planned for exhibition at Te Uru Waitākere Contemporary Gallery, Ariane notes that the Konini students placed more significance in bringing their whānau into the fold of their learnings. “The key value was always placed on their Matariki event,” says Ariane. “The gallery is a nice extra for them.”

Aotearoa presents a unique and sometimes complex conservation landscape for young minds to navigate. Toitū te Ngahereoffers creative and engaging pathways for young people to explore these complexities and to build their own personal perspective. Ariane and her team have high hopes from our upcoming kaitiaki. The more engagement that kids have when they are “really elastic in their minds” the better placed they are to invest in Aotearoa NZ’s ecosystems and to innovate real research solutions.

“It was really reaffirming to see what can happen when children are scaffolded to lead their discoveries,”

Ariane Craig-Smith.

How do young people recognise ngahere ora? Ariane believes this is problematised by a question of access. Konini have regenerating bush within their schoolgrounds, but this is unusual. Without a similar reference point, other schools would be starting their process of recognition from a very difference place.

Ariane says she is always encouraged by how engaged and passionate young people can be when they’re given the access and the tools. Of the rewards projects like Toitū te Ngahere can offer she says: “Arts can be a really useful process for slowing down and learning to observe and interpret – and to do that in quite personal ways.”

Toitū te Ngahere is funded through the Ngā Rakau Taketake research theme Mobilising for Action, in partnership with The University of Auckland.