Issie Barrett, University of Canterbury PhD student

The most common restoration technique visible along New Zealand streams is planting along the banks. While it may sound simple, riparian planting has a range of benefits, such as intercepting excess nutrients before they reach the water, and providing shade, shelter and food for invertebrates and fish.

Other restoration methods include removal of barriers such as weirs or dams, and creating perfect homes for potential stream residents by adding woody debris into the stream.

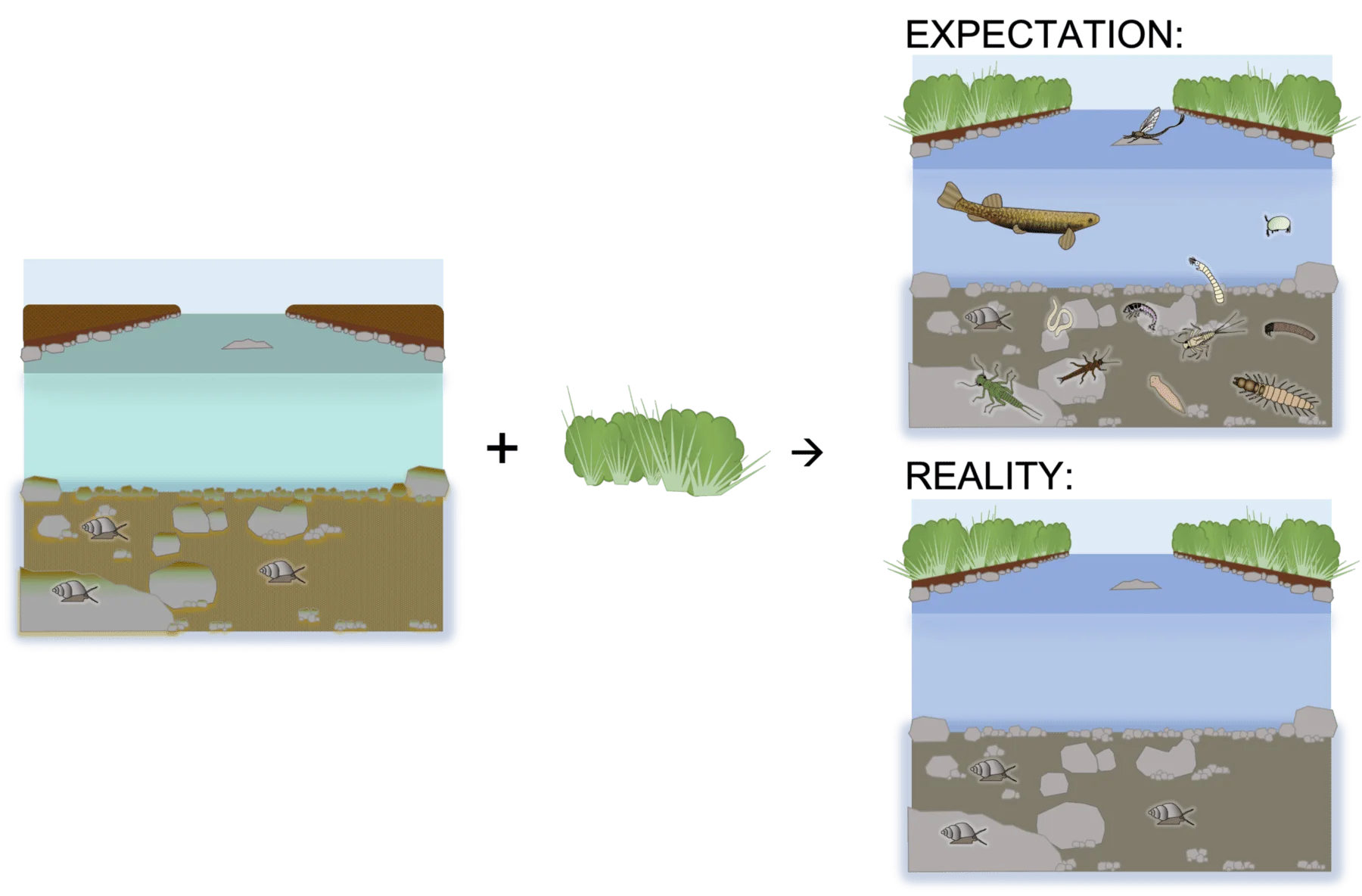

The idea is that if you rebuild habitat and restore water quality, biodiversity will return. This is known as the ‘Field of Dreams’ hypothesis, named after the 1989 movie in which Kevin Costner hears a mysterious voice telling him that ‘if you build it, he will come’. However, while Costner manages to build a baseball field and bring dead baseball players back to life, the belief that rebuilding physical habitat will lead directly to improvements in biodiversity (‘if you build it, they will come’) is almost as fantastical as the movie that inspired it.

In case after case we are yet to see life return to our waterways.

The failure of physical restoration to improve biodiversity is clear to scientists studying restoration, but this idea has not been successfully passed on to the farmers, landowners and practitioners who actually do restoration.

Many of the data and ideas that exist have become buried in complex scientific articles and impenetrable, paid-access scientific journals. Without the knowledge that restoration might not be working, let alone the effective restoration tools, there is little practitioners can do. As a restoration ecologist, this is immensely frustrating; restoration is done with such good intentions but is being limited by a disconnect between scientists and practitioners.

So what could be added to our restoration tool box to address stream community recovery?

Firstly, it is crucial to note that current physical restoration methods are critical and must still be done to enable biological recovery. There are just a few additional steps that could be taken to kickstart recovery and help species re-establish.

One method is the translocation of invertebrates and fish: moving individuals from healthy areas where they are abundant, to recovering stretches of river. This can help to boost colonisation, enabling populations to reach stable, self-sustaining levels. But this method assumes the recovering river is devoid of life. What if biodiversity isn’t returning because their newly restored home is already occupied?

In some cases, degraded stream communities can persist following physical restoration actions. These degraded communities are often dominated by hardy species who could survive poor conditions in the past and consequently proliferated. However, these species often don’t do much for ecosystem function and are not great food for fish.

A classic example is the New Zealand mud snail; if you look closely, these are often visible as the small black dots on rocks and vegetation in streams. Restoring healthy biodiversity in these situations requires extra methods to destabilise and reset the system first. This could involve artificial disturbance measures as part of restoration – as counter-intuitive as that sounds!

If we can start including these extra steps in our restoration plans, then our efforts might start producing the results we expect, and we may see healthy biodiversity return. If you build it, they will come, just with a little extra encouragement!

Issie’s research is part of the BioHeritage Tranche 1 project focused on recovery degraded waterways – find out all about it here.