Asked to name a troglobite (a cave dweller) many of us will call to mind titiwai (glow worms) or certain kinds of wētā. However, we often find colonies of Arachnocampa luminosa and Gymnoplectron (a wētā genus containing more than twenty species) living under banks and in tree hollows, while true troglobitic creatures spend their entire lives confined to cave systems.

Others will inevitably picture any of a cast of subterranean movie monsters. Maybe the pale cannibals from The Descent (2005), subway-stalking insectoids from Mimic (1997), or even more likely, Tolkien’s loathsome Gollum, described as a vile creature living deep within the Misty Mountains. But Anna Stewart knows that troglobites, or by her definition, “those animals living in subterranean air spaces”, have a bad rap. She says they’re “hidden, not horrible”.

“Our caves are super unusual to start with,” says Anna, assenting to the idea that Aotearoa’s cave systems offer us insight into alien ecosystems. “For example, we don’t have bats living in our caves.” – Both surviving endemic bat species live in forests and roost in tree hollows – “Work overseas that’s looked at cave ecology and biodiversity has often included bats. We’ve got completely different stuff going on here. Overseas scientists are super interested in our caves – because our troglobites are definitely going to be unique!” Of Aotearoa’s terrestrial troglobites, only invertebrates are known, arachnids included, with a special tilt towards the Opiliones – an order colloquially known as harvestmen and daddy longlegs.

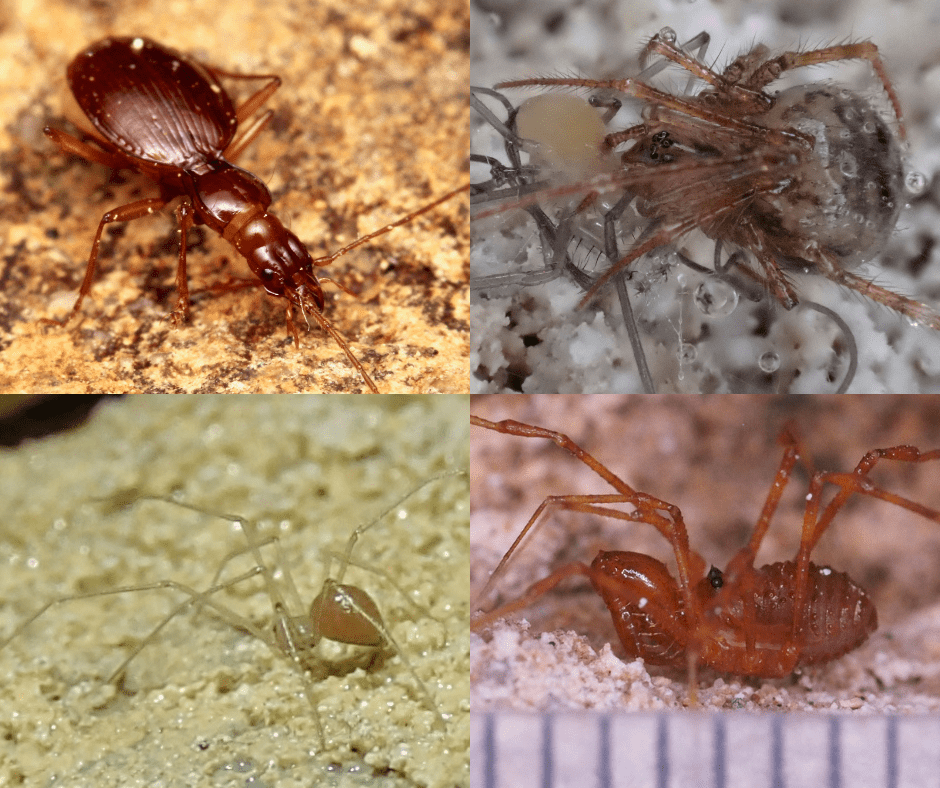

Top left: Piopio cave beetle. Top right: Tiny spider feeding on infant Forsteropsalis in Waitomo cave. Bottom left: Alpine cave spider currently being described by Te Papa’s Dr Phil Sirvid. Bottom right: Measocavern Hendea sp.

“To become a troglobite you have to have special adaptations,” says Anna. “Compared to their surface dwelling counterparts, they’re generally lighter coloured, longer limbed, have slower metabolisms, smaller size, and reduced or no eyes. Perhaps the most notable characteristic is that troglobites live longer and have fewer offspring.

When the only nutrients available are derived from the detritus that is washed in via streams and tomo (te reo Māori kupu for “sinkhole”), most troglobites grow no bigger than your thumbnail. “There’s just not the food there for anything bigger,” says Anna. “People like to think of the Nelson cave spider (Spelungula cavernicola) as a troglobite, but it’s too big for that, and would never find enough food to survive in caves full-time.”

Therein lies a challenge for Anna and her colleagues who undertake subterranean biodiversity surveys. The troglobitic lifeforms are tiny and delicate – and extremely vulnerable.

Giving the nutritional challenges presented, what benefits does cave life offer? Perhaps refuge. It’s hypothesised that troglobite ancestors ventured into caves in the first place to seek relief from stressed ecosystems above-ground. “When the outside environment is harsh, caves are a nice place to go,” says Anna.

Supporting this hypothesis, some of Anna’s favourite arachnids bear the hallmarks of ancient lineages, making other “living fossils” like tuatara look like spring chickens.

The order Rhynchocephalia, of which tuatara are the only living representatives, are thought to be some 250 million years old. But the Lomanellidae lineage (to which Synthetonychia belong) diverged from a greater Opilione superfamily (Triaenonychidae) and became distinct up to 350 million years ago! And like tuatara, Synthetonychia are only found in Aotearoa. Anna has found a cave-adapted synthetonychiid in an alpine cave, in Kahurangi National Park. It is currently being described in conjunction with Te Papa and Harvard University. Other troglobites, such as certain millipedes, are still awaiting description.

Speaking further about the benefits of cave life, Anna says “Cave life is ideal because it offers a very stable environment that can exist for millions of years, relatively unchanged, compared to the shorter-term surface ecosystems such as forests, wetlands and rivers. There’s not so much predation (predator saturation is low). The temperature is pretty constant all year round. You know where your food is coming from and what you need to do to get it.”

But these generally stable environments can make their inhabitants more vulnerable to sudden changes. The special adaptations that allow them to live in caves mean they cannot survive successfully outside of them.

The absence of bat colonies in our caves (or any know vertebrate colonies for that matter) means that the troglobitic communities don’t have the nutritional capital of guano to rely on. “They have something else,” says Anna. “I don’t know what else, but something else. They have different ways of accessing food. [Entering a cave] you’re not going to be able to find a big bat poo and see the activity going on around it. You have to look at different places.” This is a fundamental part of our cave ecosystems that we don’t yet understand.

Anna stresses that cave ecology and biodiversity in Aotearoa are poorly understood. No terrestrial troglobitic animals have ever been genetically studied here to look at possible subspecies within species or population ranges.

“Our caves are home to rare, endemic species – many awaiting discovery,” says Anna. “It is possible that these systems could be some of our oldest stable biodiversity habitats.” They should be afforded the same research, protection and conservation as all other identified areas of biodiversity.”

“Many of our limited records could be inaccurate without being able to genetically compare two different populations that may just look alike. Funding could support baseline biosurveys of caves and karst areas, collecting data, looking at distribution ranges for conservation purposes, and finding out more about troglobite history and evolution.”

As the research and conservation coordinator at The New Zealand Speleological Society (NZSS), Anna’s one of the few researchers investigating cave biodiversity at this time – so she tries to prioritise caves in areas where discoveries are helpful to landowners in the management of their land.

What does a cave visit look like for Anna? She takes her camera (with a good zoom for the tiny critters), and if she can wrangle them, other experts, like geologists and cave photographers. “Exploration is fun. It’s sporty. You can climb on stuff. Look around. You can just sit, have a coffee and enjoy the speleothems (mineral-based structures like stalactites). There’s no noise. When you turn your light off, it’s pitch black,” says Anna, who has been an avid cave explorer for twenty years.

“When you enjoy being somewhere, you want to look after it. I believe we owe a duty of care to this biodiversity habitat. Caves may be lightless, but they’re certainly not lifeless.”

Anna and the NZSS offer alluring insights into Aotearoa’s troglobites: not aliens, not monsters, but endemic lifeforms with histories that predate the Tyrannosaurus and Triceratops. With 2022 named as the International Year of the Caves & Karst, now’s the time to extend guardianship to these fascinating, and vulnerable ecosystems. You can do so by pursuing speleological research, advocating for cave conservation, and by joining the caving community.

In addition, check out Anna’s recently launched Subterranean Biodiversity webpage.

Images supplied by Anna Stewart unless otherwise stated.

Written by Kerry Donovan Brown