Matt grew up on a farm in Southland where he would play in creeks and rivers. This was his first connection with fish.

“Then, at boarding school, I used to breed tropical fish for fun,” says Matt. “I guess it was a natural progression for me to then go to the University of Otago and study zoology.”

At Otago, Matt found a great supervisor, Professor Mark Lokman, who helped Matt specialise in the reproductive physiology and captive breeding of fish like giant kōkopu (a whitebait species) and hāpuku, a type of wreckfish.

Matt’s work with hāpuku led to a stint in Vietnam working on a project involving giant grouper.

“It was an absolutely massive fish, bigger than me,” says Matt.

After that project concluded, Matt worked for Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu in Christchurch in their Research and Development team before starting a postdoc at Plant & Food Research, where he has stayed on as a permanent researcher developing the area of finfish breeding and reproductive technologies.

“At the moment, I’m supporting the development of new aquaculture species for farming – like snapper,” says Matt. “When we bring fish into captivity, they often don’t get the signals they require to synchronize spawning. Basically, my job is to understand the reproductive mysteries of fish.”

“I have also recently established a laboratory to cryopreserve (or cryobank) sperm from fish – whether that be from elite families we have bred for aquaculture, or from threatened and culturally significant freshwater species like whitebait.”

Over the course of his career, Matt has built a web of connections with other researchers and groups who share his passion.

“When I was at Otago, my supervisor was very good at connecting me with people that he knew, which really helped the stepping-stones of my career.”

Kanakana captive breeding and translocation

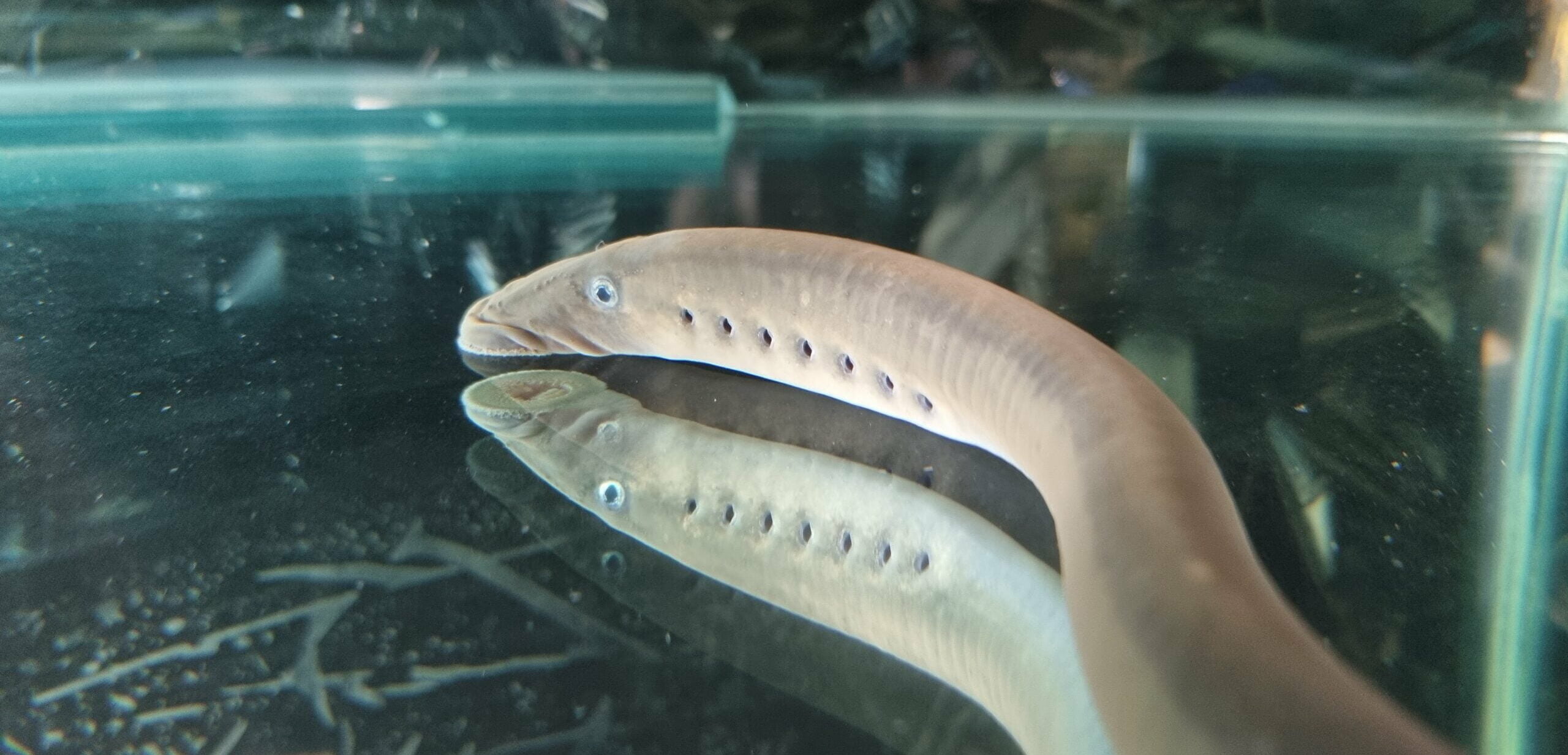

Through his ability to connect, Matt has found himself working within the Freshwater for our Taonga BioHeritage project that supports Hokonui Rūnanga around their aspirations of developing captive breeding and translocation processes for kanakana (pouched lamprey).

“I’m really enjoying being able to work on the kanakana project because it’s driven by the mana whenua of Hokonui,” says Matt. “I think my colleagues would agree that we’re just the scientists, pulling in our expertise and what we know to support the vision of mana whenua.”

By centring on Indigenous expertise and aspirations, the team aims to understand the technical, social and cultural aspects of captive breeding and translocating kanakana.

“We all envision a more holistic and just captive breeding and translocation process,” says Matt.

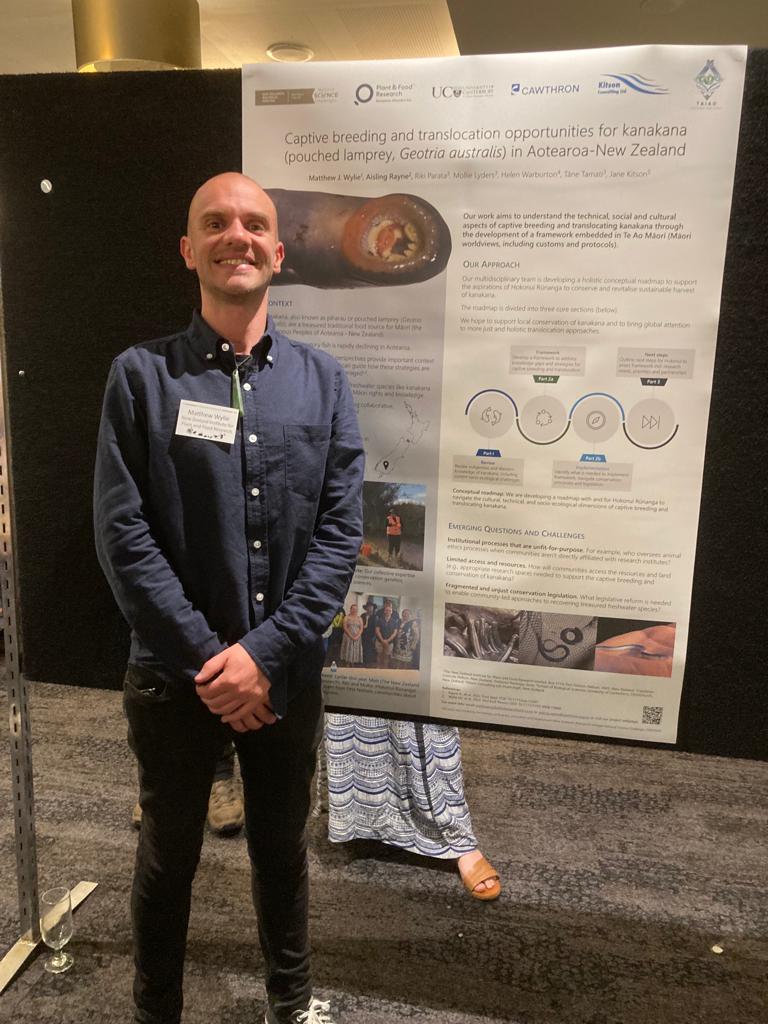

Through assistance from a Ngā Pī Ka Rere grant, Matt was able to present this research with colleague Aisling Rayne at the 3rd International Conservation Translocation Conference in Perth last year.

Matt couldn’t help but notice how underrepresented fish were at the conference.

“There were posters of tropical birds, gorillas and all these beautiful animals,” says Matt. “We had a slimy kanakana on our poster, which we of course thought was quite cute.”

Matt found that Indigenous peoples were also underrepresented.

“Through the Hokonui Rūnanga-led project, we connect with First Nation communities in the USA who are really leading Pacific lamprey conservation and captive breeding initiatives over there,” says Matt. “But overall, I’d say Indigenous communities aren’t particularly well represented in these spaces.”

Matt sees conferences as the perfect opportunity to make new connections. He has this piece of advice to offer to early career individuals.

“At conferences, go and talk to the big scary famous people – the ones whose papers you are always reading. Even if you feel like an annoying student or emerging researcher, try and connect with them. Because I did, and I now work with some of the most amazing fish people in our field.”

Jenny Leonard