Alison Greenaway and Andrea Grant, social scientists within the Ngā Rākau Taketake theme Mobilising for Action, are actively seeking ways to accommodate the messiness of the world in the way science is communicated.

“Science-based abstraction can make our world appear oversimplified or too linear and detach from people’s experiences,” says Andrea.

“By tidying up the world too much, science narratives can lose people’s trust,” says Alison. “We use people’s stories, their own words, to help keep science connected.”

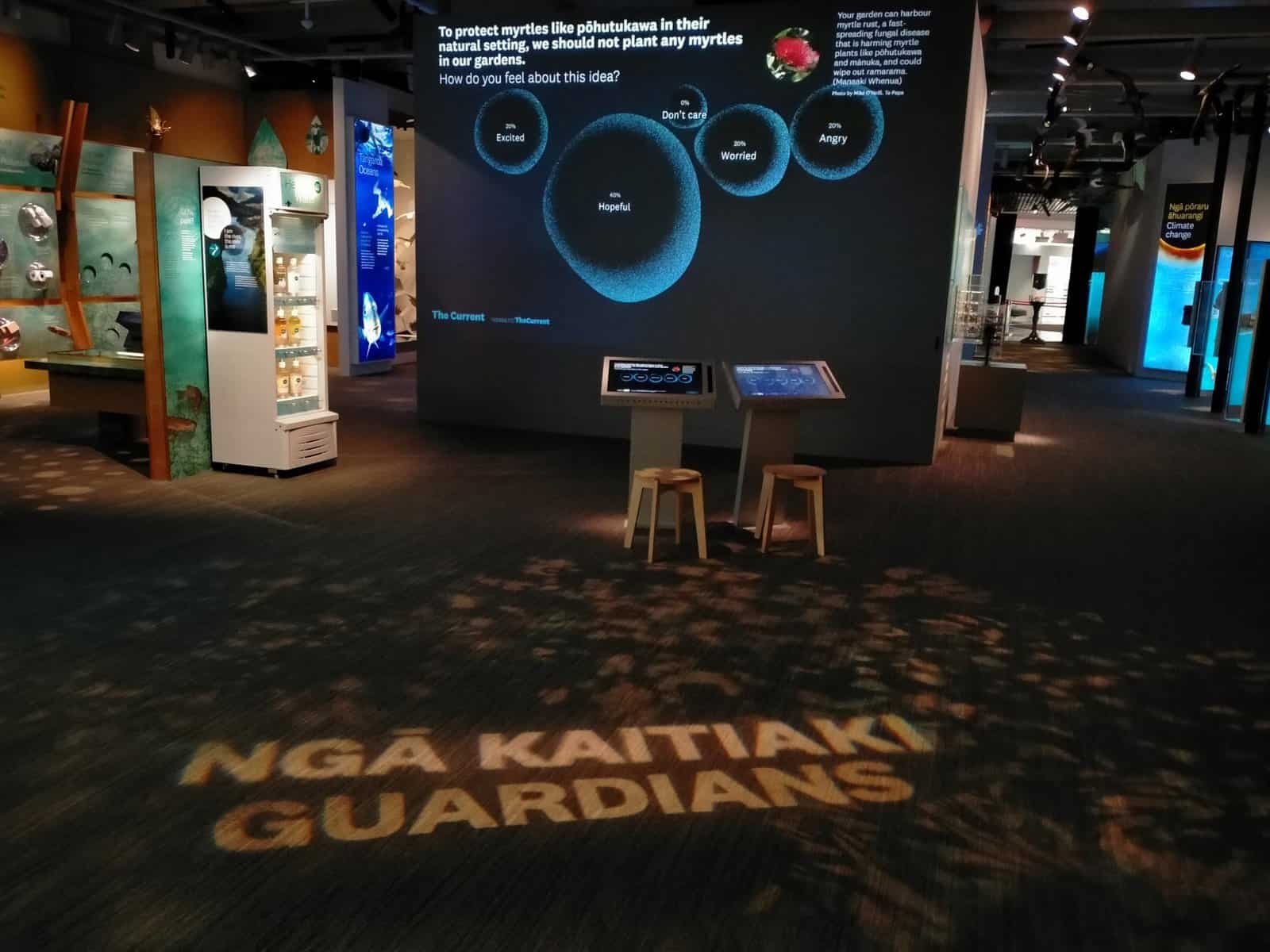

One way they are gathering stories is through the Te Taiao | Nature exhibition in the Te Papa museum. The exhibit is an interactive, hands-on way to engage people in science and the environment. One feature of the exhibit is a set of “provocations” – statements designed to provoke contemplation of current challenges we are facing in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Alison and Andrea were part of a team of writers, scientists, social scientists and mātauranga Māori curators who designed two provocations addressing kauri dieback and myrtle rust. The provocations were:

- “We should protect kauri, even if that means we’ll never get to walk in a kauri forest again.”

- “To protect myrtles like pōhutukawa in their natural setting, we should not plant any myrtles in our gardens.”

After each provocation, which were presented in English and te reo Māori, the question “How do you feel about this idea?” was posed. People were asked to select Excited, Hopeful, Worried, Don’t Care, or Angry. They were also given a chance to explain why they felt this way through an open-ended written response.

“The answers provided give an indication of the different sets of values about nature that people hold,” says Alison. “It also shows the different ways people articulate their care and their concern for kauri and myrtles, the ngāhere (forests) and te taiao (environment).”

The team is now experimenting with how to share the information that has been gathered with policy and decision makers, their research collaborators, and the public. For example, they have shared the written responses with Māori artists to see how these sentiments and emotions might be interpreted and brought to life in artistic representations.

“Having these responses opens up inquiries with Māori and with multiple ways of seeing the world that have typically sat outside of the science system,” says Andrea.

“This project has become a pathway to better understand different ways of representing different knowledge systems.”

Having more information about the knowledge held across our society and where this knowledge comes from can help researchers ask better questions.

“The way we ask questions about the world influences what is possible to change in the world,” says Alison.

While Alison and Andrea hope that this kind of work will strengthen how science engages with people, they also hope it will strengthen people’s relationship with science.

“This social research helps us to know more about the effects of the narratives we tell each other about the natural world and our relationships with it,” says Alison.

Alison and Andrea would love to hear from you. You can start a conversation with them by emailing Alison at and Andrea at .