Cryobanking is a process of freezing live cells for future use. In a conservation context, this practice has proven useful for enhancing the genetic diversity of threatened species and reducing the negative impacts of inbreeding. One frequently cited success of cryobanking is a US project where black-footed ferret genetic diversity has been successfully improved using frozen sperm for assisted reproduction and, more recently, frozen cells for cloning, giving this critically endangered species a higher level of resilience in the face of future change.

Given the benefits that cryobanking could provide to Aotearoa New Zealand’s conservation efforts, the NEXT Foundation, DOC, BioHeritage and Genomics Aotearoa funded a two-year proof-of-concept project that Tāpui Aotearoa ran through 2021-2022.

“The goal of the project was to investigate what cryobanking would look like in New Zealand,” says Libby Caygill, a geneticist by training who spearheaded the project.

“One part of this was reviewing what we are already technically capable of, what is already being done in New Zealand and what samples of our indigenous fauna are represented in international collections.”

The project identified several main challenges that would need to be overcome if a cryobank were to be established to serve New Zealand conservation purposes. One key challenge is technical.

“The scientific community knows a lot about mammalian cryobanking,” says Libby. “We know far less about birds, reptiles and amphibians.”

Another key challenge is social.

“Any cryobanking project in Aotearoa would have to keep Te Tiriti at its heart,” says Libby. “A huge part of this project has been working on the recognition and preservation of Māori tino rangatiratanga and kaitiakitanga in relation to any stored samples.”

Libby sees this as one of the major benefits of establishing a New Zealand-led cryobanking effort.

“We’ve been able to control and design this project and make it a Te Tiriti-led project instead of relying on international consortiums using their own rules to keep our taonga safe,” says Libby. “We’d prefer to collect, store and manage samples on our terms.”

Tāpui Aotearoa completed a draft business plan at the end of 2022. The goal is to proactively sample and store material from Aotearoa’s unique fauna at a stage when there is still a reasonable degree of genetic diversity in the population. Libby sums it up as “an insurance policy against future events that could threaten species survival”.

In 2023, Libby and the team hope to establish longer-term funding commitments, bring on board philanthropic funds and establish initial iwi partnerships to test their operating principles.

“Cryobanking is an intergenerational project,” says Libby. “Because of that, our success will hinge on whether we are able to build strong, resilient partnerships.”

Once funding is secured and partnerships have been started, Tāpui Aotearoa will be able to turn their attention to the technical challenges of cryobanking in the New Zealand context.

“The expertise is out there, we just need to grow our capability in New Zealand,” says Libby.

BioHeritage is proud to have contributed to the solid foundation Tāpui Aotearoa has built for themselves and wishes them well for a promising period of growth ahead.

“We would really like to thank BioHeritage and all our initial funders for their support,” says Libby. “Without the contributions towards those initial two years, we couldn’t have even started thinking about what possibilities cryobanking could lend to New Zealand. We’ve come a long way.”

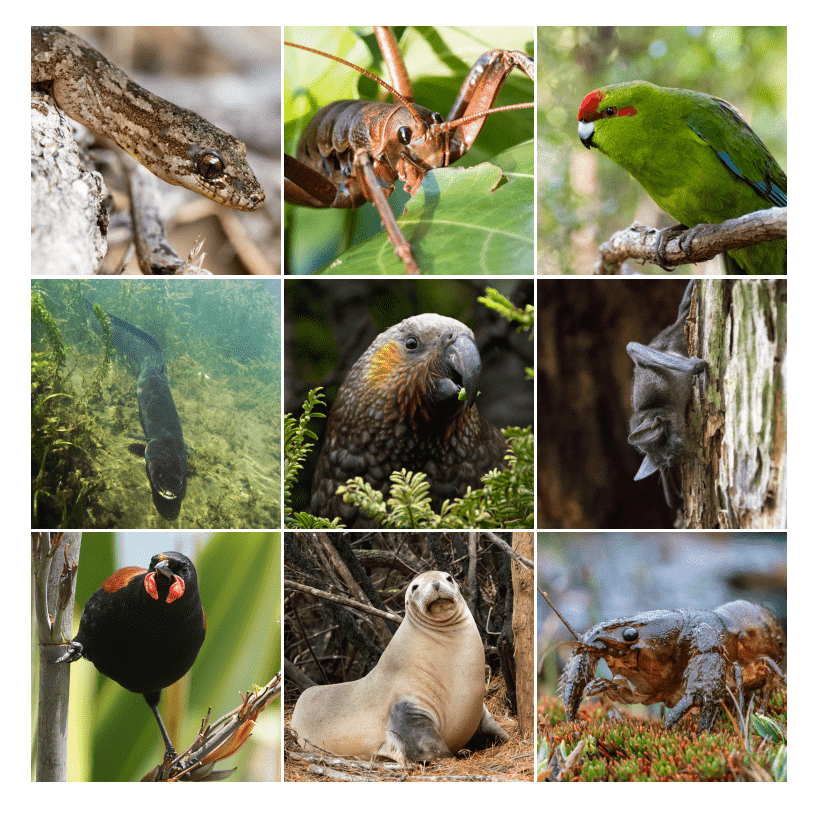

Image credits (for top of page):

- Pacific Gecko (Dactylocnemis pacificus). Jake Osborne

- Wētāpunga/giant wētā (Deinacrida heteracantha). Jake Osbourne

- Kākāriki/red-crowned parakeet (Cyanoramphus novaezelandiae). Jake Osborne

- Tuna/New Zealand longfin eel (Anguilla dieffenbachii). EOS Ecology

- Kākā (Nestor meridionalis). Tomas Sobek

- Pekapeka-tou-poto/southern short-tailed bat (Mystacina tuberculata). Jake Osbourne

- Tīeke/North Island Saddleback (Philesturnus rufusater). David Cook

- Rāpoka/New Zealand Sea Lion (Phocarctos hookeri). Jake Osbourne

- Kōura/New Zealand fresh water crayfish (Paranephrops zealandicus). Jake Osborne

– Jenny Leonard